Lipid metabolism refers to the biochemical processes by which the body digests, absorbs, transports, synthesizes, and breaks down lipids to meet its energy and structural needs.

Lipids are the most energy-dense biomolecules, providing more than twice the energy of carbohydrates and proteins, making lipid metabolism essential for survival, especially during fasting and prolonged exercise.

In addition to serving as a major fuel source, lipids are vital components of cell membranes, hormones, bile acids, and signaling molecules.

From an exam perspective, lipid metabolism is a core topic in biochemistry, medical, pharmacy, nursing, and life-science curricula.

Questions commonly focus on pathways such as fatty acid oxidation, fatty acid synthesis, cholesterol metabolism, and ketone body formation, along with their regulation and associated disorders.

Clinically, abnormalities in lipid metabolism are linked to conditions like obesity, diabetes mellitus, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular disorders.

This article provides a clear, step-by-step explanation of lipid metabolism, covering key pathways, regulatory mechanisms, hormonal control, and clinical significance—making it useful for both conceptual understanding and exam preparation.

What Is Lipid Metabolism?

Lipid metabolism is the collective term for all biochemical reactions involved in the digestion, absorption, transport, synthesis, and degradation of lipids in the human body.

These processes allow the body to efficiently use lipids as a major source of energy, structural components, and signaling molecules.

In simple terms, lipid metabolism explains how fats from the diet are processed, stored, converted into energy, or used to build essential cellular components.

Types of Lipids Involved in Lipid Metabolism

Lipid metabolism primarily involves the following classes of lipids:

- Fatty acids – the main energy-rich molecules oxidized to produce ATP

- Triglycerides – the major storage form of lipids in adipose tissue

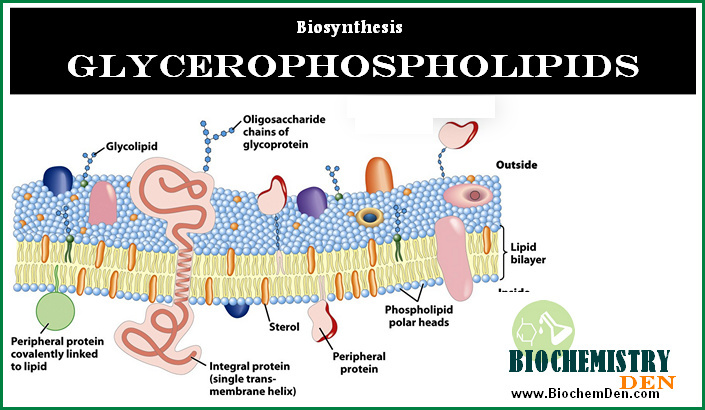

- Phospholipids – key structural components of cell membranes

- Cholesterol – required for membrane fluidity, steroid hormone synthesis, bile acids, and vitamin D

Each of these lipids follows specific metabolic pathways depending on the body’s energy status and physiological needs.

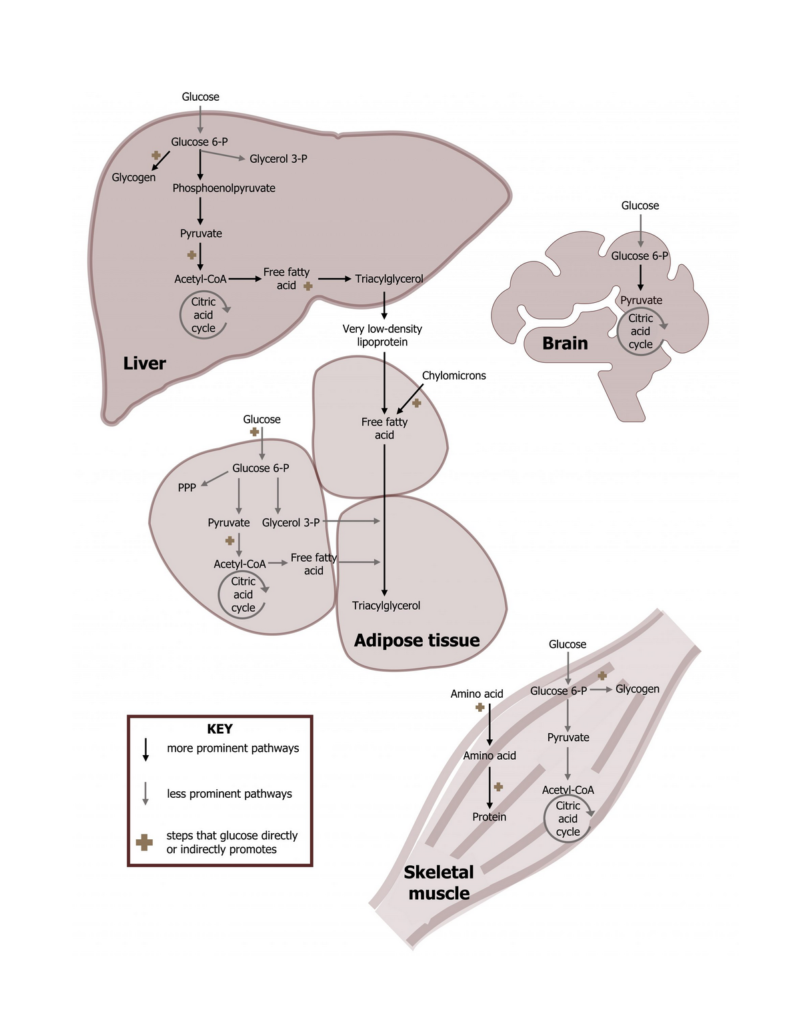

Major Organs Involved in Lipid Metabolism

Lipid metabolism is a coordinated process involving multiple organs:

- Intestine – digestion and absorption of dietary lipids

- Liver – central hub for lipid synthesis, oxidation, cholesterol metabolism, and lipoprotein formation

- Adipose tissue – storage of triglycerides and release of fatty acids during fasting

- Skeletal muscle – oxidation of fatty acids for energy, especially during prolonged activity

Anabolic and Catabolic Pathways

Lipid metabolism includes both:

- Anabolic pathways, such as fatty acid synthesis and triglyceride formation, which store energy

- Catabolic pathways, such as β-oxidation and ketone body formation, which release energy

These pathways are tightly regulated and often operate reciprocally.

Key Objectives of Lipid Metabolism

The main objectives of lipid metabolism in the body are:

- To provide a high-yield energy source during fasting and starvation

- To store excess energy efficiently as triglycerides

- To supply structural lipids for cell membranes

- To produce biologically important molecules like hormones and bile acids

Understanding lipid metabolism is essential for grasping both normal physiology and the biochemical basis of metabolic disorders, making it a fundamental topic in biochemistry and clinical studies.

| Feature | β-Oxidation | Fatty Acid Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Mitochondria | Cytosol |

| Function | Breakdown | Synthesis |

| Carrier | Carnitine | ACP |

| Reducing agent | FAD, NAD⁺ | NADPH |

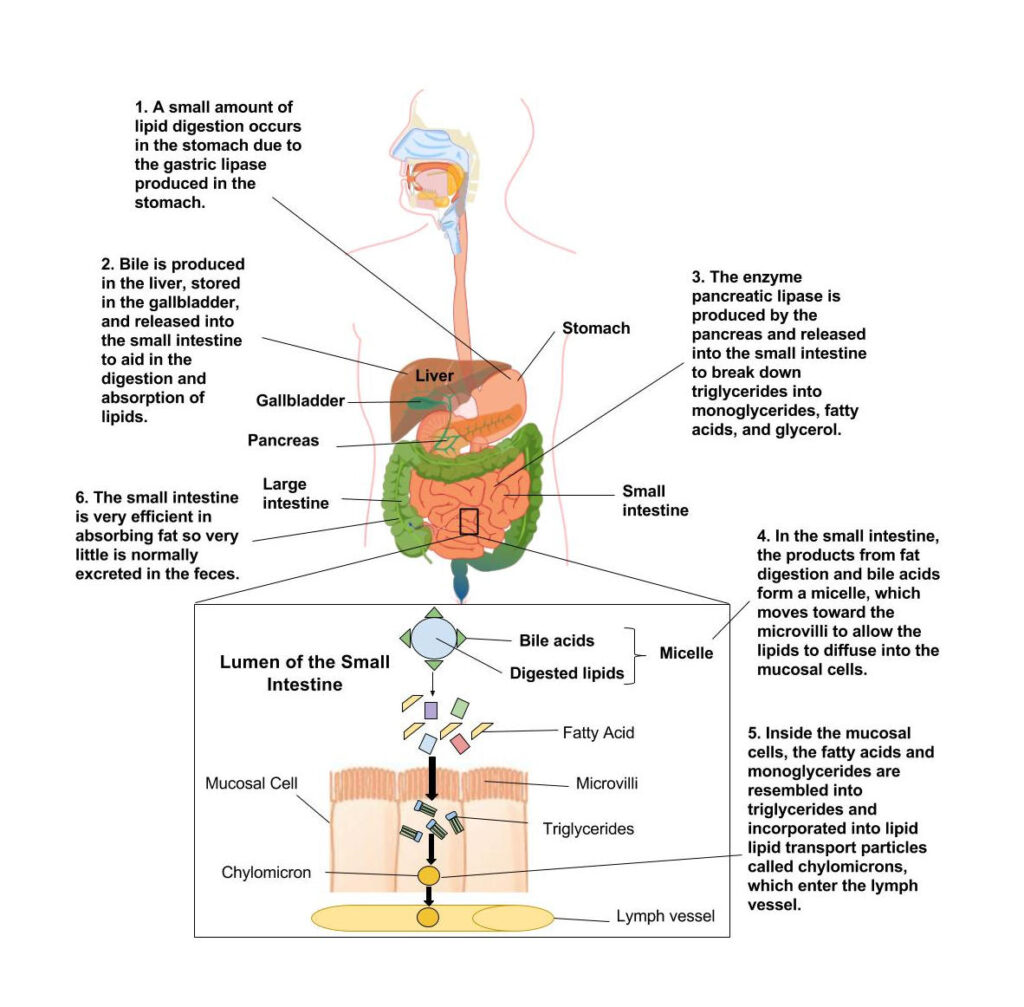

Digestion and Absorption of Lipids

Digestion and absorption of lipids is the first and most crucial step in lipid metabolism, as dietary fats must be broken down into absorbable forms before they can be utilized for energy, storage, or biosynthesis.

Because lipids are hydrophobic, their digestion requires specialized mechanisms involving bile salts, enzymes, and transport structures.

This process mainly occurs in the small intestine and is highly relevant for understanding both normal physiology and clinical disorders related to fat malabsorption.

Dietary Sources of Lipids

Dietary lipids are mainly obtained from:

- Triglycerides (major component of dietary fat)

- Phospholipids

- Cholesterol and cholesterol esters

These lipids are commonly found in oils, butter, dairy products, meat, eggs, nuts, and seeds. Among them, triglycerides account for nearly 90–95% of dietary lipids and are the primary target of digestive enzymes.

Role of Bile Salts in Emulsification

Since lipids are insoluble in water, their digestion begins with emulsification by bile salts, which are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and secreted into the intestine via bile.

Bile salts:

- Reduce the surface tension of large fat globules

- Break them into smaller droplets

- Increase the surface area for enzyme action

This emulsification step is essential for efficient lipid digestion and is a common focus in exam questions on lipid metabolism.

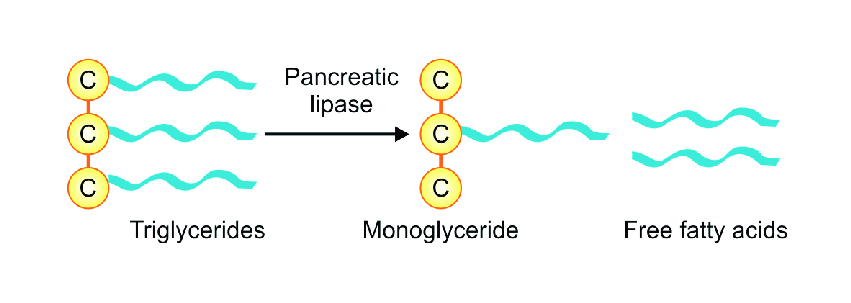

Action of Pancreatic Lipase

The key enzyme involved in lipid digestion is pancreatic lipase, which acts primarily on emulsified triglycerides.

Pancreatic lipase:

- Hydrolyzes triglycerides into free fatty acids and 2-monoglycerides

- Requires the presence of bile salts and colipase for optimal activity

This step converts complex lipids into simpler molecules that are suitable for absorption.

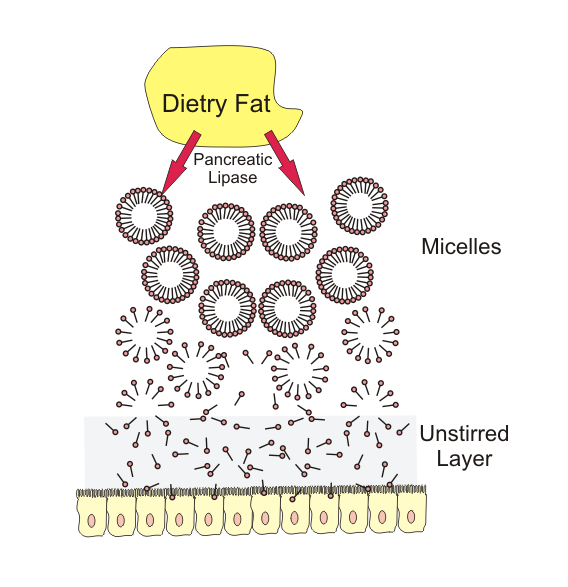

Formation of Micelles

The products of lipid digestion—free fatty acids, monoglycerides, cholesterol, and fat-soluble vitamins—combine with bile salts to form mixed micelles.

Micelles:

- Are water-soluble aggregates

- Transport lipid digestion products to the intestinal mucosal surface

- Facilitate diffusion across the intestinal brush border

Micelle formation is a critical link between lipid digestion and absorption.

Absorption of Fatty Acids and Monoglycerides in Intestinal Cells

At the intestinal epithelium:

- Fatty acids and monoglycerides diffuse into enterocytes

- Bile salts remain in the intestinal lumen and are later reabsorbed (enterohepatic circulation)

Inside the enterocytes, these lipid components are directed toward metabolic processing and transport.

Re-esterification and Chylomicron Formation

Within intestinal cells:

- Fatty acids and monoglycerides are re-esterified to form triglycerides

- Triglycerides combine with cholesterol, phospholipids, and apolipoproteins to form chylomicrons

Chylomicrons are lipoproteins responsible for transporting dietary lipids from the intestine to peripheral tissues via the lymphatic system and bloodstream, playing a central role in lipid transport.

Clinical Note: Fat Malabsorption

Impairment in lipid digestion or absorption leads to fat malabsorption, which may occur due to:

- Bile salt deficiency

- Pancreatic enzyme insufficiency

- Intestinal mucosal damage

Clinically, fat malabsorption results in steatorrhea, weight loss, and deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), highlighting the medical importance of proper lipid digestion and absorption.

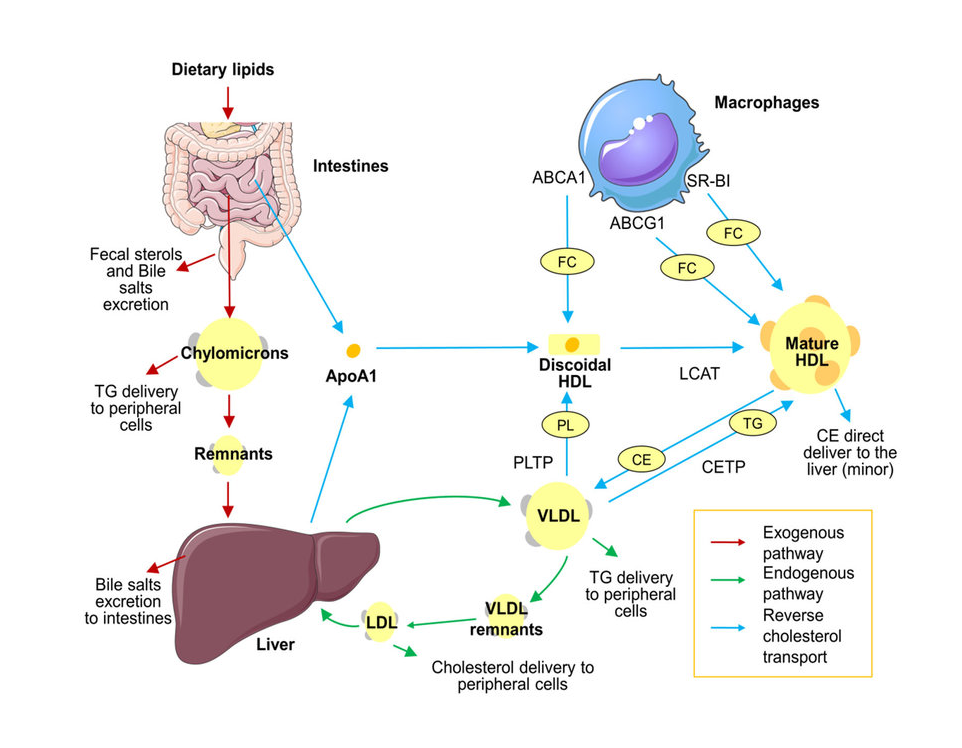

Transport of Lipids (Chylomicrons, VLDL, LDL, HDL)

After digestion and absorption, lipids must be transported efficiently through the bloodstream to reach various tissues.

Since lipids are insoluble in water, they cannot circulate freely in plasma. To overcome this, the body packages lipids into specialized complexes called lipoproteins, which play a central role in lipid metabolism and clinical disorders related to cholesterol and triglycerides.

Lipoproteins in Lipid Transport

Lipids such as triglycerides and cholesterol are hydrophobic and therefore require carrier molecules for transport in the aqueous environment of blood. Lipoproteins act as transport vehicles that:

- Carry dietary and endogenous lipids through circulation

- Deliver triglycerides and cholesterol to tissues

- Maintain lipid homeostasis

- Prevent lipid aggregation in plasma

Without lipoproteins, lipid transport and utilization would be physiologically impossible.

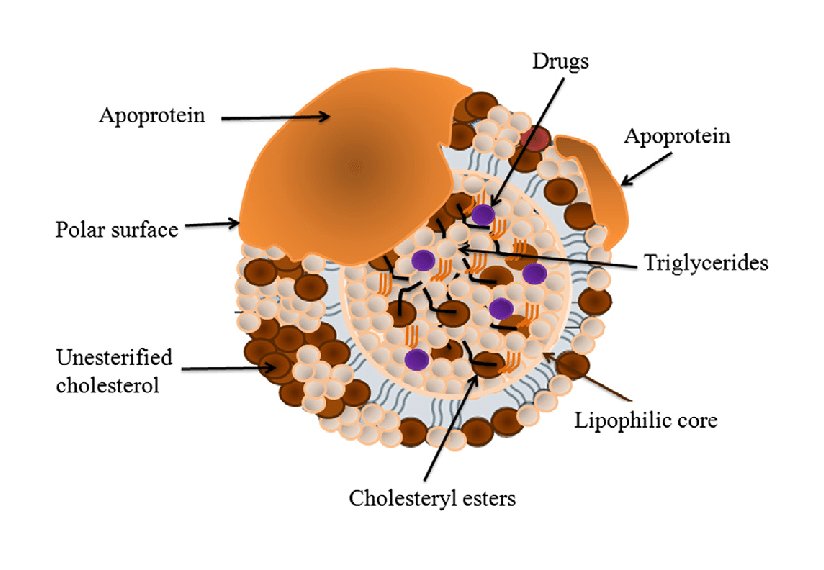

Structure of Lipoproteins

All lipoproteins share a common structural organization consisting of:

Core (hydrophobic):

- Triglycerides

- Cholesterol esters

Surface (hydrophilic):

- Phospholipids

- Free cholesterol

- Apolipoproteins

This amphipathic structure allows lipoproteins to remain soluble in blood while safely transporting lipids.

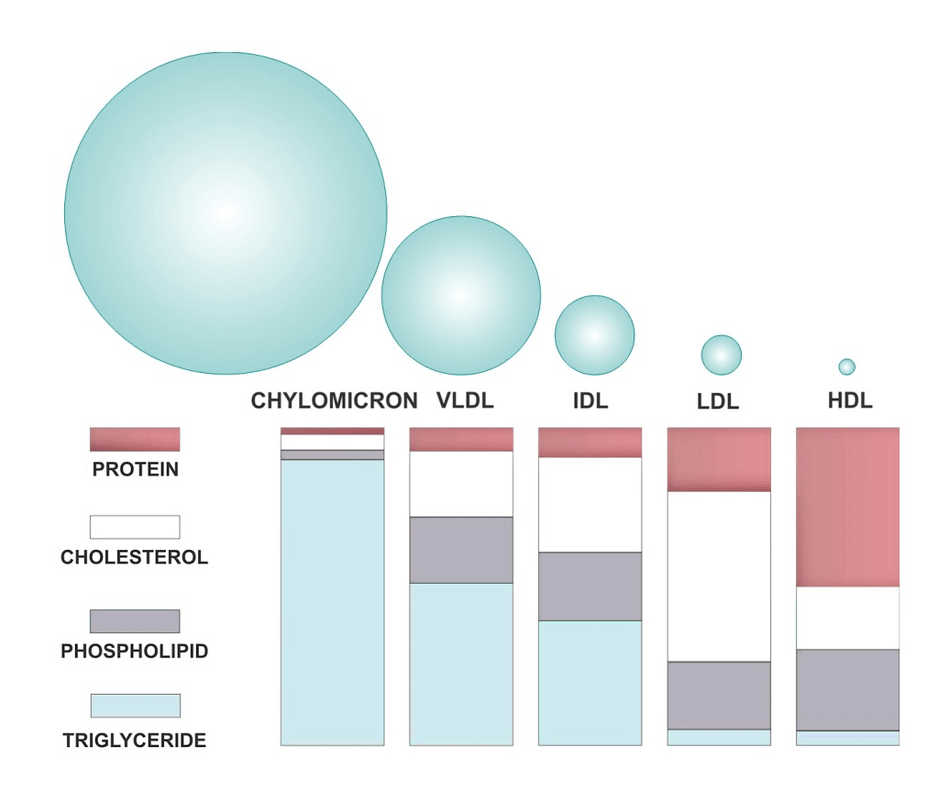

1. Chylomicrons – Transport of Dietary Lipids

Chylomicrons are the largest and least dense lipoproteins formed in intestinal mucosal cells after lipid absorption.

- Rich in dietary triglycerides

- Transport lipids from the intestine to peripheral tissues

- Enter circulation via the lymphatic system

- Triglycerides are hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase

Chylomicron remnants are taken up by the liver, linking dietary lipid intake with hepatic lipid metabolism.

2. VLDL – Transport of Endogenous Triglycerides

Very Low-Density Lipoproteins (VLDL) are synthesized in the liver and transport endogenously produced triglycerides.

- Deliver triglycerides from the liver to muscle and adipose tissue

- Converted into IDL and eventually LDL after triglyceride removal

- Important in maintaining energy supply during fasting

Elevated VLDL levels are commonly associated with hypertriglyceridemia.

3. LDL – Cholesterol Delivery to Tissues

Low-Density Lipoproteins (LDL) are formed from VLDL remnants and are the primary carriers of cholesterol in the blood.

- Deliver cholesterol to peripheral tissues

- Cholesterol is used for membrane synthesis and steroid hormones

- Excess LDL leads to cholesterol deposition in arterial walls

LDL is commonly referred to as “bad cholesterol” due to its strong association with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

4. HDL – Reverse Cholesterol Transport

High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL) play a protective role in lipid metabolism.

- Collect excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues

- Transport cholesterol back to the liver for excretion

- Help prevent plaque formation in arteries

Because of this function, HDL is known as “good cholesterol” and is inversely related to cardiovascular risk.

Apolipoproteins and Their Functions

Apolipoproteins are protein components of lipoproteins that:

- Provide structural stability

- Act as enzyme cofactors

- Serve as ligands for lipoprotein receptors

Examples include:

- Apo B-48 (chylomicrons)

- Apo B-100 (VLDL and LDL)

- Apo A-I (HDL)

Clinical Relevance: Good vs Bad Cholesterol

The balance between LDL and HDL levels is a key indicator of cardiovascular health:

- High LDL → increased risk of atherosclerosis

- High HDL → protective effect against heart disease

Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism are central to conditions such as hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, and metabolic syndrome, making lipid transport an essential topic in both biochemistry and clinical medicine.

Fatty Acid Oxidation (β-Oxidation)

Fatty acid oxidation, commonly known as β-oxidation, is a major catabolic pathway of lipid metabolism through which fatty acids are broken down to generate energy.

This pathway is especially important during fasting, prolonged exercise, and starvation, when carbohydrates are limited, and lipids become the primary fuel source.

β-oxidation converts long-chain fatty acids into acetyl-CoA, which enters the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation to produce ATP.

Definition and Purpose of β-Oxidation

β-oxidation is the stepwise degradation of fatty acids in which two-carbon units are removed from the β-carbon of the fatty acyl-CoA molecule during each cycle.

The main purposes of β-oxidation are:

- To generate ATP for cellular energy

- To supply acetyl-CoA for the TCA cycle and ketone body formation

- To maintain energy homeostasis during low-glucose conditions

Because fatty acids yield more energy per gram than carbohydrates, β-oxidation is a highly efficient energy-producing pathway.

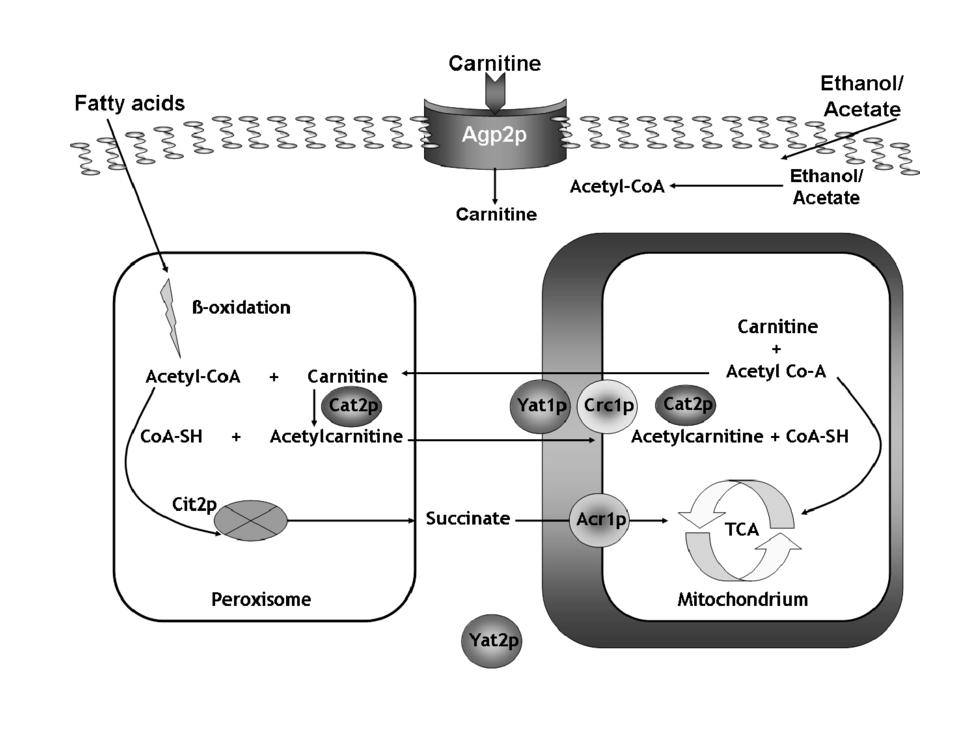

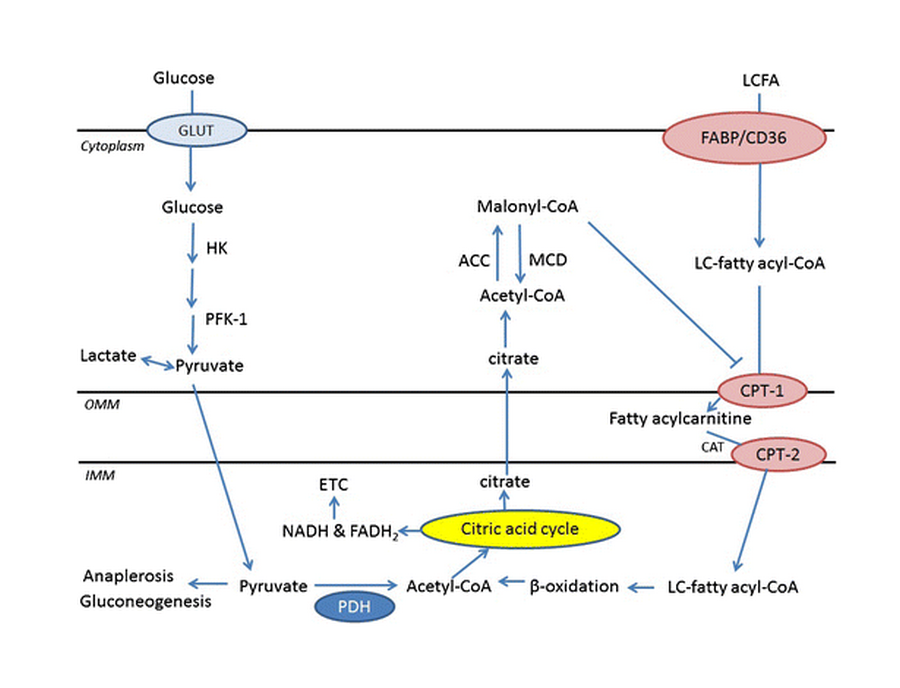

Cellular and Subcellular Location

Fatty acid oxidation occurs mainly in:

- Mitochondrial matrix – site of β-oxidation for short-, medium-, and long-chain fatty acids

- Peroxisomes – oxidation of very long-chain fatty acids (initial shortening)

This compartmentalization is frequently tested in biochemistry examinations.

Activation of Fatty Acids

Before oxidation, fatty acids must be activated in the cytosol.

- Enzyme involved: Fatty acyl-CoA synthetase (thiokinase)

- Fatty acid + CoA + ATP → Fatty acyl-CoA

- ATP is converted to AMP + PPi (equivalent to 2 ATP consumed)

Activation is an essential preparatory step in fatty acid metabolism.

Carnitine Shuttle Mechanism

Long-chain fatty acids cannot cross the inner mitochondrial membrane directly and require the carnitine shuttle system.

Steps involved:

- Formation of fatty acyl-carnitine by CPT-I (Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-I)

- Transport across the inner mitochondrial membrane

- Regeneration of fatty acyl-CoA by CPT-II

This step is a key regulatory point of β-oxidation and is inhibited by malonyl-CoA during fatty acid synthesis.

Steps of β-Oxidation

Each cycle of β-oxidation consists of four recurring reactions:

1. Oxidation

- Enzyme: Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- Formation of a trans double bond

- FAD is reduced to FADH₂

2. Hydration

- Enzyme: Enoyl-CoA hydratase

- Addition of water across the double bond

3. Second Oxidation

- Enzyme: β-Hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- NAD⁺ is reduced to NADH

4. Thiolysis

- Enzyme: Thiolase

- Cleavage releases acetyl-CoA and a shortened fatty acyl-CoA

The shortened fatty acyl-CoA re-enters the cycle until complete oxidation is achieved.

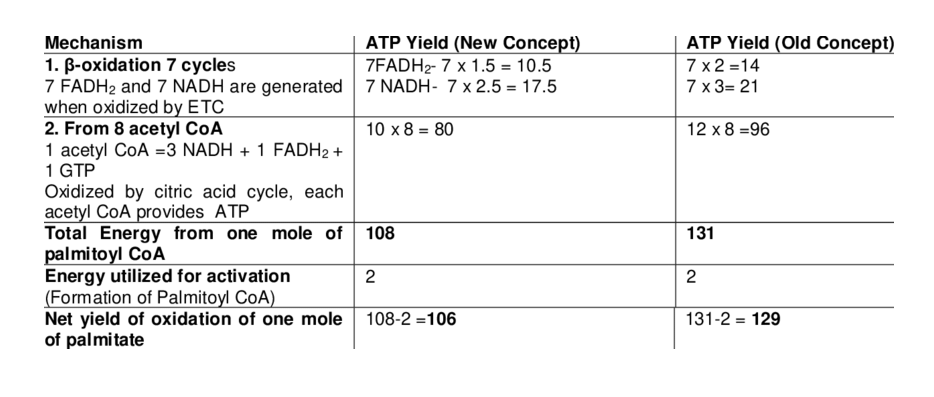

Energy Yield: ATP Calculation for Palmitic Acid

Palmitic acid (C₁₆:₀) undergoes 7 cycles of β-oxidation, producing:

- 8 acetyl-CoA

- 7 FADH₂

- 7 NADH

Total ATP yield:

- From the TCA cycle: 8 × 10 = 80 ATP

- From FADH₂: 7 × 1.5 = 10.5 ATP

- From NADH: 7 × 2.5 = 17.5 ATP

- Total = 108 ATP

- Minus activation cost (2 ATP)

- Net yield = 106 ATP

This high ATP yield explains why fats are superior energy stores.

Regulation of β-Oxidation

β-oxidation is tightly regulated to prevent futile cycling.

Key regulatory mechanisms include:

- CPT-I inhibition by malonyl-CoA

- Hormonal regulation (glucagon ↑, insulin ↓)

- Availability of free fatty acids

- NADH/NAD⁺ ratio in mitochondria

This coordination ensures balance between fatty acid synthesis and breakdown.

Disorders Related to β-Oxidation

Defects in fatty acid oxidation lead to serious metabolic disorders, including:

- Carnitine deficiency

- Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency

- Hypoglycemia during fasting

- Muscle weakness and lethargy

Clinically, impaired β-oxidation can result in energy deficiency, especially in tissues like the heart and skeletal muscle.

Fatty Acid Synthesis

Fatty acid synthesis is an anabolic pathway of lipid metabolism in which excess carbohydrates and proteins are converted into fatty acids for long-term energy storage.

This process is most active in the fed state, when energy supply is abundant, and insulin levels are high.

Fatty acid synthesis plays a central role in maintaining energy balance and is especially important in the liver, adipose tissue, and lactating mammary glands.

Purpose and Significance of Fatty Acid Synthesis

The primary purpose of fatty acid synthesis is to:

- Store excess energy efficiently as triglycerides

- Provide fatty acids for membrane lipids

- Support the synthesis of signaling molecules and hormones

Unlike β-oxidation, which releases energy, fatty acid synthesis is a biosynthetic pathway that consumes ATP and reducing power.

Site of Fatty Acid Synthesis

Fatty acid synthesis occurs in the:

- Cytosol of cells

- Mainly in the liver

- Also in adipose tissue and mammary glands

This cytosolic location is an important distinguishing feature when compared with mitochondrial β-oxidation.

Source of Acetyl-CoA and NADPH

Acetyl-CoA, required for fatty acid synthesis, is generated in the mitochondria but must be transported to the cytosol:

- Acetyl-CoA combines with oxaloacetate to form citrate

- Citrate is transported to the cytosol

- ATP-citrate lyase releases acetyl-CoA in the cytosol

NADPH, the reducing agent for fatty acid synthesis, is supplied by:

- Pentose phosphate pathway

- Malic enzyme reaction

Both acetyl-CoA and NADPH are essential substrates in lipid biosynthesis.

Formation of Malonyl-CoA (Committed Step)

The rate-limiting and committed step of fatty acid synthesis is the conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA.

- Enzyme: Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC)

- Cofactors: Biotin, ATP, CO₂

- Regulation: Activated by insulin and citrate; inhibited by glucagon and fatty acids

Malonyl-CoA also inhibits CPT-I, preventing simultaneous fatty acid oxidation.

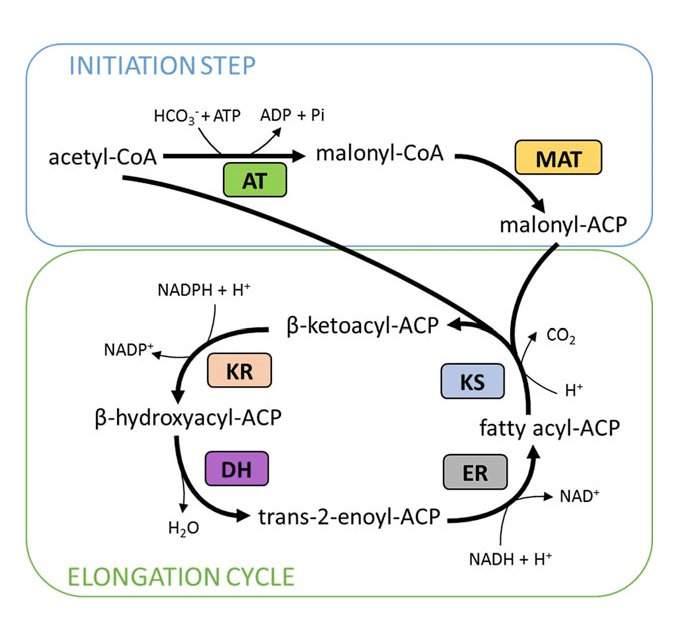

Fatty Acid Synthase Complex

Fatty acid synthesis is carried out by a large multifunctional enzyme complex called fatty acid synthase (FAS).

- Acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA are attached to acyl carrier protein (ACP)

- The growing fatty acid chain remains bound to ACP throughout synthesis

The coordinated activity of multiple enzymatic domains allows efficient chain elongation.

Steps of Fatty Acid Synthesis

Each cycle of fatty acid synthesis involves:

- Condensation of acetyl and malonyl groups

- Reduction using NADPH

- Dehydration

- Second reduction using NADPH

Each cycle adds two carbon atoms to the growing fatty acid chain until palmitic acid (C₁₆:₀) is formed.

Overall Reaction and Energy Requirement

The synthesis of palmitic acid requires:

- 8 acetyl-CoA

- 7 ATP

- 14 NADPH

This high energy demand highlights that fatty acid synthesis is an energy-consuming process, occurring only when energy is abundant.

Regulation of Fatty Acid Synthesis

Fatty acid synthesis is tightly regulated at multiple levels:

- Hormonal regulation: Insulin stimulates, glucagon inhibits

- Allosteric regulation: Citrate activates ACC

- Feedback inhibition: Long-chain fatty acids inhibit ACC

- Reciprocal regulation with β-oxidation via malonyl-CoA

This ensures coordination between lipid storage and lipid breakdown.

Physiological and Clinical Relevance

Excessive fatty acid synthesis contributes to:

- Obesity

- Fatty liver disease

- Insulin resistance

Conversely, proper regulation of fatty acid synthesis is essential for maintaining metabolic health.

Cholesterol Metabolism

Cholesterol metabolism is a vital component of lipid metabolism that maintains an adequate supply of cholesterol for normal cellular functions while preventing its harmful accumulation.

Cholesterol is an essential lipid molecule required for cell membrane integrity, steroid hormone synthesis, bile acid formation, and vitamin D production. Because excess cholesterol is strongly associated with cardiovascular disease, its synthesis, transport, and excretion are tightly regulated.

Functions of Cholesterol in the Body

Cholesterol performs several essential physiological roles:

- Maintains membrane fluidity and stability

- Precursor for steroid hormones such as cortisol, aldosterone, estrogen, and testosterone

- Required for bile acid and bile salt synthesis

- Precursor of vitamin D

Despite its importance, cholesterol cannot be oxidized to produce energy, making regulation crucial.

Sources of Cholesterol

Cholesterol in the body comes from two main sources:

- Dietary cholesterol absorbed from animal-based foods

- Endogenous cholesterol synthesis, primarily in the liver

The liver plays a central role in balancing cholesterol input, utilization, and excretion.

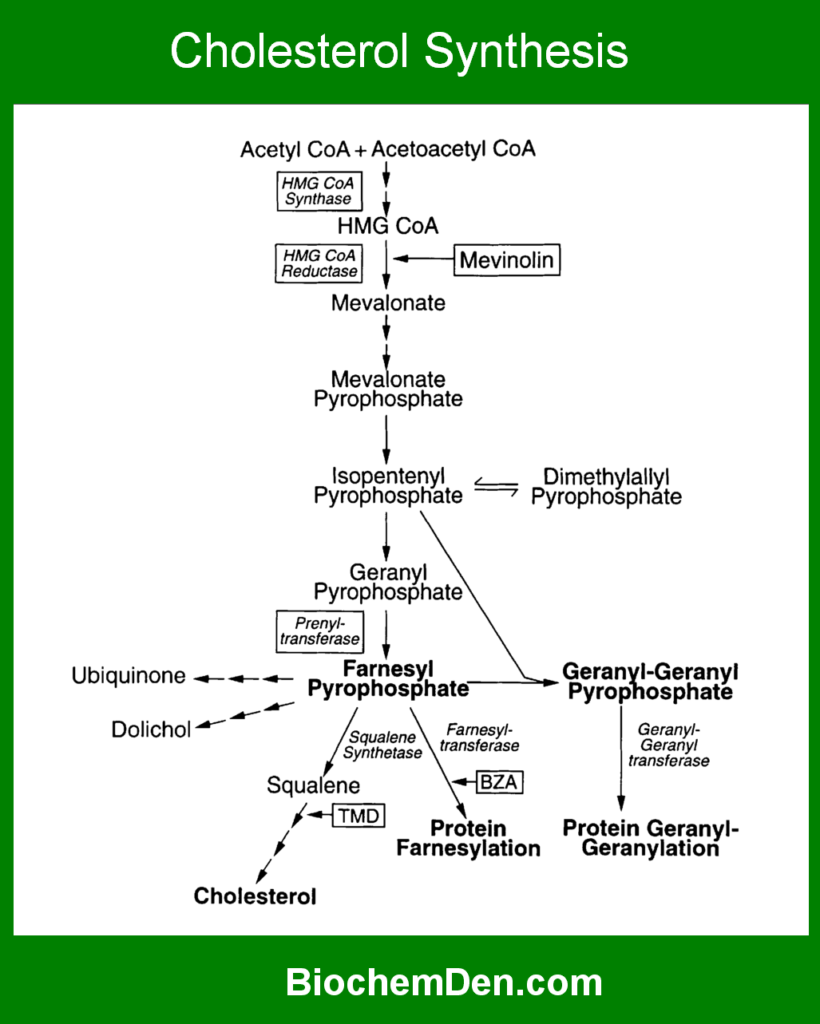

Cholesterol Biosynthesis

Cholesterol synthesis occurs mainly in the cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum of liver cells.

Key Steps of Cholesterol Biosynthesis

- Formation of HMG-CoA from acetyl-CoA

- Conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate

- Formation of activated isoprene units

- Condensation to form squalene

- Cyclization of squalene to form cholesterol

Rate-Limiting Enzyme and Regulation

The most important regulatory step in cholesterol metabolism is catalyzed by:

- HMG-CoA reductase (rate-limiting enzyme)

Regulation occurs through:

- Feedback inhibition by cholesterol

- Hormonal control (insulin ↑, glucagon ↓)

- Covalent modification (phosphorylation)

- Pharmacological inhibition by statins

This step is a frequent target in exams and clinical discussions.

Transport of Cholesterol

Cholesterol is transported in the blood as part of lipoproteins:

- LDL delivers cholesterol to peripheral tissues

- HDL removes excess cholesterol and returns it to the liver

An imbalance between LDL and HDL levels leads to cholesterol accumulation in arterial walls.

Conversion to Bile Acids and Excretion

Cholesterol is eliminated from the body mainly by:

- Conversion to bile acids and bile salts in the liver

- Excretion via bile into the intestine

This is the only significant pathway for cholesterol removal, emphasizing the importance of hepatic cholesterol metabolism.

Clinical Relevance of Cholesterol Metabolism

Disorders of cholesterol metabolism are directly linked to:

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Atherosclerosis

- Coronary artery disease

Elevated LDL cholesterol increases cardiovascular risk, whereas HDL cholesterol provides a protective effect.

Ketone Body Formation and Utilization

Ketone body formation and utilization are important adaptive pathways of lipid metabolism that provide an alternative source of energy during periods of fasting, starvation, prolonged exercise, and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

When carbohydrate availability is low and fatty acid oxidation is high, excess acetyl-CoA produced in the liver is converted into ketone bodies. These water-soluble molecules can cross the blood–brain barrier and serve as a vital fuel for extrahepatic tissues, especially the brain.

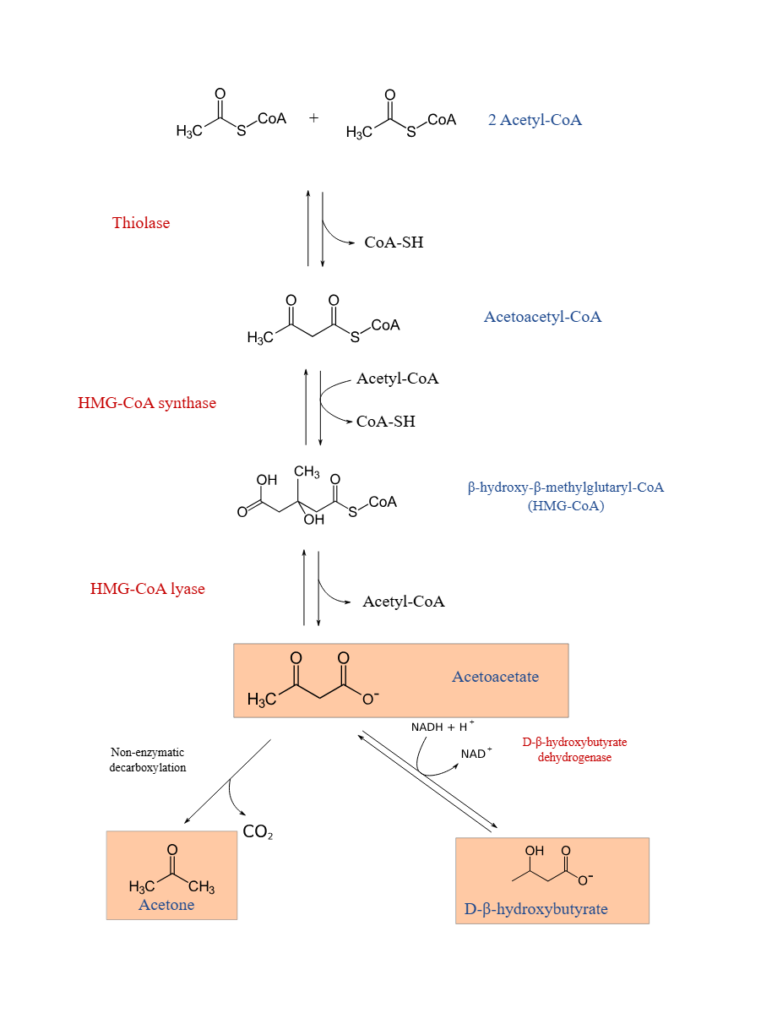

What Are Ketone Bodies?

Ketone bodies are small, water-soluble molecules derived from acetyl-CoA. The three main ketone bodies are:

- Acetoacetate

- β-Hydroxybutyrate

- Acetone

Among these, acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate are metabolically active, while acetone is excreted via breath and urine.

Conditions Favoring Ketone Body Formation

Ketogenesis occurs when carbohydrate metabolism is reduced, and lipid metabolism predominates, such as in:

- Prolonged fasting or starvation

- Uncontrolled type 1 diabetes mellitus

- Low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets

- Prolonged endurance exercise

These conditions increase fatty acid oxidation, leading to the accumulation of acetyl-CoA in the liver.

Site of Ketone Body Formation

Ketone bodies are synthesized exclusively in the mitochondrial matrix of liver cells.

Although the liver produces ketone bodies, it cannot utilize them due to the absence of a key enzyme required for ketone body utilization.

Steps of Ketone Body Formation (Ketogenesis)

Ketogenesis involves the following major steps:

- Condensation of two acetyl-CoA molecules

- Formation of HMG-CoA

- Cleavage of HMG-CoA to produce acetoacetate

- Conversion of acetoacetate to β-hydroxybutyrate or acetone

This pathway helps divert excess acetyl-CoA away from the TCA cycle.

Transport of Ketone Bodies

Once synthesized, ketone bodies:

- Are released into the bloodstream

- Travel to extrahepatic tissues

- Do not require lipoproteins or albumin for transport

Their water solubility makes them efficient circulating fuels.

Utilization of Ketone Bodies (Ketolysis)

Ketone body utilization occurs in extrahepatic tissues, such as:

- Brain (during prolonged fasting)

- Heart muscle

- Skeletal muscle

- Renal cortex

Ketone bodies are converted back into acetyl-CoA, which enters the TCA cycle to generate ATP.

Physiological Importance of Ketone Bodies

Ketone bodies play a crucial role in:

- Sparing glucose during fasting

- Reducing protein breakdown

- Providing energy to the brain when glucose is scarce

This adaptive mechanism supports survival during energy deprivation.

Clinical Relevance: Ketoacidosis

Excessive production of ketone bodies can lead to ketoacidosis, particularly in uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

- Characterized by metabolic acidosis

- Elevated blood ketone levels

- Fruity odor of breath due to acetone

Understanding ketone body metabolism is essential for interpreting metabolic disorders in clinical practice.

Regulation of Lipid Metabolism

Regulation of lipid metabolism ensures a balanced coordination between lipid synthesis, storage, and breakdown according to the body’s energy needs.

Because lipids are high-energy molecules, their metabolism must be tightly controlled to prevent unnecessary energy loss or excessive fat accumulation.

The regulation of lipid metabolism integrates nutritional status, enzyme activity, and hormonal signals, allowing the body to switch efficiently between fed and fasting states.

Need for Regulation

Lipid metabolism includes both anabolic pathways (fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis) and catabolic pathways (fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis).

If these pathways were active simultaneously, it would result in futile cycling and energy wastage. Therefore, regulation is essential to:

- Match lipid metabolism with energy demand

- Maintain metabolic homeostasis

- Prevent metabolic disorders

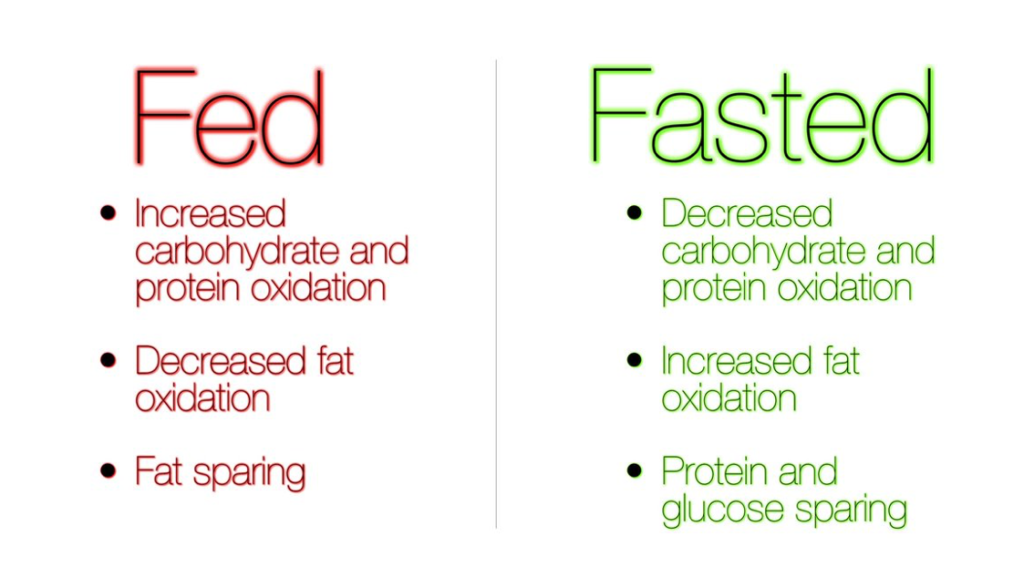

Fed State vs Fasting State

The body regulates lipid metabolism differently depending on nutritional status:

Fed State

- High glucose and insulin levels

- Increased fatty acid synthesis

- Increased triglyceride storage

- Decreased fatty acid oxidation

Fasting State

- Low glucose and insulin levels

- Increased lipolysis in adipose tissue

- Increased fatty acid oxidation and ketone body formation

- Reduced lipid synthesis

This metabolic switching is a common exam topic.

Enzyme-Level Regulation

Key enzymes act as control points in lipid metabolism:

- Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC)

- Rate-limiting enzyme of fatty acid synthesis

- Activated by citrate

- Inhibited by long-chain fatty acids

- Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-I (CPT-I)

- Controls the entry of fatty acids into mitochondria

- Inhibited by malonyl-CoA

These enzymes help ensure reciprocal regulation of lipid synthesis and oxidation.

Allosteric Regulation

Allosteric effectors provide rapid regulation of lipid metabolism:

- Citrate activates fatty acid synthesis when energy is abundant

- Malonyl-CoA inhibits fatty acid oxidation

- High NADH/NAD⁺ ratio slows β-oxidation

Such regulation allows immediate metabolic adjustments.

Covalent Modification

Many lipid metabolism enzymes are regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation:

- Phosphorylation (via AMP-activated protein kinase) generally inhibits lipid synthesis

- Dephosphorylation promotes anabolic pathways

This mechanism links lipid metabolism to cellular energy status.

Reciprocal Regulation of Lipid Pathways

A key principle in lipid metabolism is reciprocal regulation, meaning:

- When fatty acid synthesis is active, β-oxidation is inhibited

- When β-oxidation is active, fatty acid synthesis is suppressed

Malonyl-CoA plays a central role in coordinating this balance.

Physiological Significance

Proper regulation of lipid metabolism:

- Maintains normal body weight

- Supports energy supply during fasting

- Prevents excessive lipid accumulation

Dysregulation contributes to obesity, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease.

Hormonal Control of Lipid Metabolism

Hormonal control of lipid metabolism plays a decisive role in regulating lipid synthesis, storage, mobilization, and oxidation in response to the body’s nutritional and energy status.

Hormones act as chemical messengers that coordinate lipid metabolism across different tissues, ensuring that energy is stored during abundance and released during scarcity.

The most important hormones involved are insulin, glucagon, epinephrine, and cortisol, each exerting specific effects on lipid metabolic pathways.

Role of Insulin in Lipid Metabolism

Insulin is the primary anabolic hormone that promotes lipid storage during the fed state.

- Stimulates fatty acid synthesis in the liver

- Activates acetyl-CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase

- Increases triglyceride synthesis in adipose tissue

- Inhibits hormone-sensitive lipase, reducing lipolysis

Overall, insulin favors lipid storage and energy conservation.

Role of Glucagon in Lipid Metabolism

Glucagon acts mainly during fasting and stress conditions.

- Stimulates lipolysis in adipose tissue

- Enhances fatty acid oxidation in the liver

- Promotes ketone body formation

- Inhibits fatty acid synthesis

Glucagon shifts metabolism toward energy mobilization.

Role of Epinephrine (Adrenaline)

Epinephrine is released during acute stress and physical activity.

- Activates hormone-sensitive lipase

- Rapidly increases lipolysis

- Supplies free fatty acids to muscles for energy

- Acts through cAMP-mediated phosphorylation

This hormone supports immediate energy demands.

Role of Cortisol

Cortisol is a long-acting stress hormone that influences lipid metabolism indirectly.

- Promotes lipolysis in adipose tissue

- Enhances the availability of fatty acids

- Supports gluconeogenesis by sparing glucose

Chronic elevation of cortisol can contribute to fat redistribution and metabolic disorders.

Integrated Hormonal Regulation

Hormonal control of lipid metabolism is coordinated and tissue-specific:

- Insulin dominance → lipid synthesis and storage

- Glucagon and epinephrine dominance → lipid mobilization and oxidation

This balance ensures metabolic flexibility.

Clinical Significance

Hormonal imbalance can disrupt lipid metabolism and lead to:

- Obesity

- Diabetes mellitus

- Dyslipidemia

- Metabolic syndrome

Understanding hormonal control is essential for both biochemistry exams and clinical diagnosis.

Disorders of Lipid Metabolism

Disorders of lipid metabolism arise when there is an imbalance in lipid digestion, transport, synthesis, or breakdown.

These disorders can be inherited or acquired and are commonly associated with abnormal levels of triglycerides and cholesterol in the blood, leading to serious metabolic and cardiovascular complications.

Understanding these disorders is essential for linking biochemical pathways with clinical conditions.

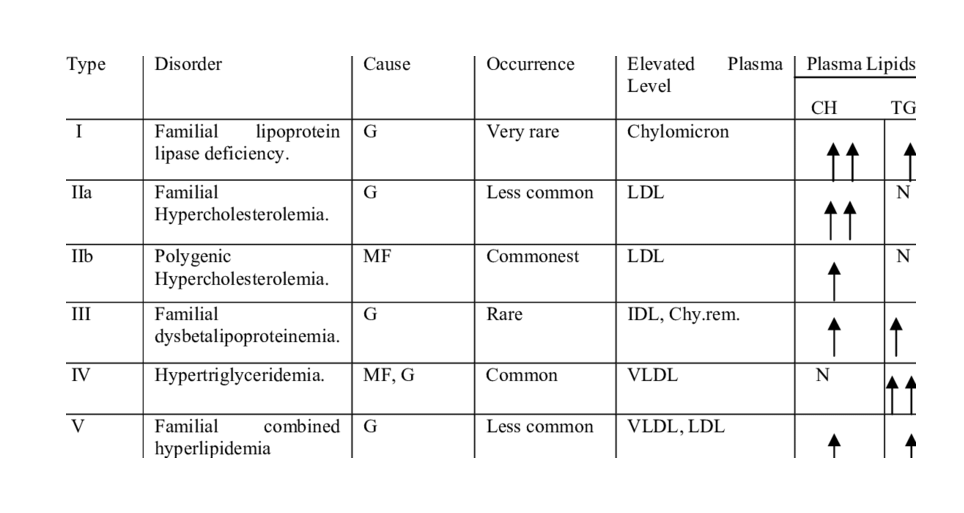

Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia is characterized by elevated levels of lipids in the blood, particularly cholesterol and triglycerides.

- Caused by genetic defects or lifestyle factors

- Often associated with increased LDL and VLDL levels

- Major risk factor for atherosclerosis

Primary hyperlipidemias result from enzyme or receptor defects, while secondary forms are linked to diabetes, obesity, and hypothyroidism.

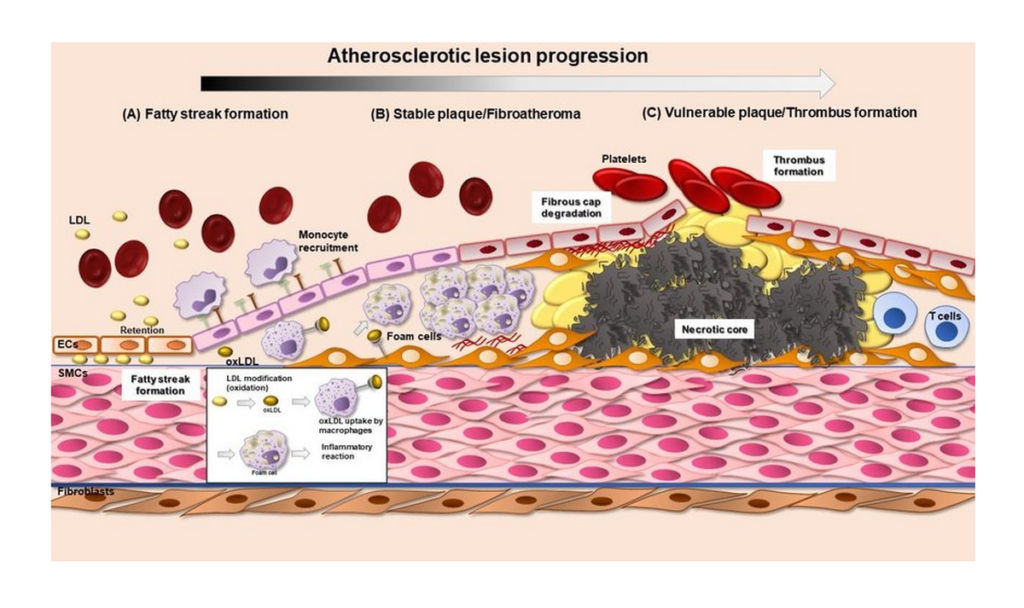

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a chronic condition caused by cholesterol deposition in arterial walls.

- LDL cholesterol accumulates in blood vessels

- Formation of atherosclerotic plaques

- Leads to reduced blood flow

This condition is a leading cause of coronary artery disease and stroke.

Fatty Liver Disease

Fatty liver disease occurs due to excessive accumulation of triglycerides in liver cells.

- Common in obesity and insulin resistance

- Associated with increased fatty acid synthesis

- Impairs normal liver function

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is closely linked to metabolic syndrome.

Carnitine Deficiency

Carnitine deficiency affects fatty acid oxidation.

- Impairs transport of long-chain fatty acids into mitochondria

- Causes muscle weakness and hypoglycemia

- Common in infants and genetic disorders

This condition highlights the importance of the carnitine shuttle in lipid metabolism.

Inherited Lipid Metabolism Disorders

Several inherited disorders result from enzyme deficiencies, such as:

- Familial hypercholesterolemia

- Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency

- Lipoprotein lipase deficiency

These disorders often present early in life and require biochemical diagnosis.

Clinical Importance

Disorders of lipid metabolism contribute significantly to:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Obesity

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Early diagnosis and lifestyle intervention are crucial for effective management.

Clinical Significance of Lipid Metabolism

The clinical significance of lipid metabolism lies in its direct connection with many of the most common and serious metabolic and cardiovascular disorders seen in medical practice. Any disturbance in lipid digestion, transport, synthesis, or breakdown can lead to abnormal lipid levels in blood and tissues, resulting in both acute and chronic diseases. For this reason, lipid metabolism forms a crucial link between biochemistry, pathology, and clinical diagnosis.

1. Role of Lipid Metabolism in Cardiovascular Diseases

Abnormal lipid metabolism is a major underlying cause of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).

- Elevated LDL cholesterol promotes cholesterol deposition in arterial walls

- Reduced HDL cholesterol impairs reverse cholesterol transport

- Increased triglycerides contribute to plaque instability

These changes lead to atherosclerosis, narrowing of blood vessels, reduced blood flow, and increased risk of heart attack and stroke. Therefore, lipid metabolism is central to understanding coronary artery disease and hypertension.

2. Importance of Lipid Metabolism in Obesity and Diabetes

Lipid metabolism plays a key role in the development of obesity and diabetes mellitus.

- Excess fatty acid synthesis leads to increased triglyceride storage in adipose tissue

- Impaired fatty acid oxidation promotes fat accumulation

- Elevated free fatty acids cause insulin resistance

In type 2 diabetes, altered lipid metabolism worsens hyperglycemia and increases cardiovascular risk, making lipid control an essential part of diabetes management.

3. Lipid Metabolism in Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions closely linked to abnormal lipid metabolism.

- Increased triglycerides

- Decreased HDL cholesterol

- Central obesity

- Insulin resistance

Dysregulation of lipid metabolism in metabolic syndrome significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Understanding lipid metabolism helps explain why lifestyle modification is a cornerstone of treatment.

4. Diagnostic Markers Related to Lipid Metabolism

Clinical evaluation of lipid metabolism relies on biochemical markers measured in blood.

Common diagnostic tests include:

- Total cholesterol

- LDL cholesterol

- HDL cholesterol

- Triglycerides

- VLDL cholesterol

Abnormal lipid profiles help diagnose dyslipidemia, assess cardiovascular risk, and monitor the effectiveness of therapy.

5. Importance of Lipid Metabolism in Clinical Biochemistry

Lipid metabolism is a foundational topic in clinical biochemistry because:

- It explains the biochemical basis of common diseases

- It guides the interpretation of lipid profile tests

- It helps in understanding drug actions, such as statins

- It supports evidence-based diagnosis and treatment

For students and clinicians, a strong understanding of lipid metabolism bridges the gap between biochemical pathways and real-world clinical applications.

Lipid Metabolism vs Carbohydrate Metabolism

Lipid metabolism and carbohydrate metabolism are the two major energy-producing systems in the human body.

While both pathways are tightly interconnected, they differ significantly in terms of energy yield, storage capacity, hormonal regulation, and metabolic priority during fasting and fed states.

Understanding these differences is especially important for biochemistry exams and for explaining metabolic adaptations in health and disease.

Comparison of Energy Yield

One of the most important differences between lipid and carbohydrate metabolism is the amount of energy produced.

- Lipids provide approximately 9 kcal per gram, making them the most energy-dense macronutrients

- Carbohydrates provide about 4 kcal per gram

Fatty acid oxidation yields significantly more ATP than glucose oxidation. For example, complete oxidation of palmitic acid produces far more ATP than oxidation of a single glucose molecule. This high energy yield makes lipids ideal for long-term energy storage.

Storage Forms: Fat vs Glycogen

The body stores excess energy differently depending on the macronutrient:

- Lipids are stored as triglycerides in adipose tissue

- Carbohydrates are stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles

Triglycerides are stored in a nearly anhydrous form, allowing large amounts of energy to be stored efficiently. In contrast, glycogen binds water, making carbohydrate storage bulky and limited.

As a result, lipid metabolism supports long-term energy reserves, whereas carbohydrate metabolism supports short-term energy needs.

Hormonal Regulation Differences

Hormonal control differs markedly between lipid and carbohydrate metabolism:

- Insulin promotes glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, and fatty acid synthesis

- Glucagon and epinephrine stimulate glycogen breakdown, lipolysis, and fatty acid oxidation

Carbohydrate metabolism responds rapidly to changes in blood glucose levels, while lipid metabolism responds more gradually, supporting sustained energy release. This coordinated regulation ensures metabolic flexibility.

Metabolic Priority During Fasting

During different nutritional states, the body prioritizes one pathway over the other:

- Fed state: Carbohydrate metabolism predominates; glucose is the primary fuel

- Early fasting: Glycogen breakdown supplies glucose

- Prolonged fasting or starvation: Lipid metabolism becomes dominant, with fatty acid oxidation and ketone body utilization

This shift protects blood glucose levels and spares protein breakdown, highlighting the survival importance of lipid metabolism.

Functional Role in Different Tissues

- Brain: Primarily uses glucose; adapts to ketone bodies during prolonged fasting

- Muscle: Uses both glucose and fatty acids depending on activity and availability

- Adipose tissue: Specialized for lipid storage and mobilization

- Liver: Central organ coordinating both lipid and carbohydrate metabolism

This tissue-specific utilization emphasizes the complementary roles of the two pathways.

Simple Comparison Table: Lipid vs Carbohydrate Metabolism

| Feature | Lipid Metabolism | Carbohydrate Metabolism |

|---|---|---|

| Energy yield | High (9 kcal/g) | Moderate (4 kcal/g) |

| Storage form | Triglycerides | Glycogen |

| Storage capacity | Very large | Limited |

| Water requirement | Minimal | High |

| Primary role | Long-term energy supply | Short-term energy supply |

| Dominant during | Fasting, starvation | Fed state |

| Hormonal control | Glucagon, insulin | Insulin, glucagon |

Clinical and Exam Relevance

Understanding the differences between lipid metabolism and carbohydrate metabolism helps explain:

- Why is fat the main energy source during fasting

- The metabolic basis of diabetes and obesity

- Adaptive responses to starvation and endurance exercise

For students, this comparison is frequently tested in short notes, long answers, and viva questions, making it a high-yield topic in biochemistry.

FAQs on Lipid Metabolism

What is lipid metabolism in simple terms?

Lipid metabolism is the process by which the body digests, absorbs, transports, stores, and breaks down fats to produce energy and support essential functions. It explains how dietary fats are converted into usable forms or stored for future energy needs.

Why is lipid metabolism important for the body?

Lipid metabolism is important because lipids are the most concentrated source of energy in the body. It also supports cell membrane structure, hormone production, bile acid formation, and long-term energy storage, especially during fasting and starvation.

Which organs are mainly involved in lipid metabolism?

The major organs involved in lipid metabolism are the intestine, liver, adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle. The intestine absorbs dietary lipids, the liver regulates synthesis and transport, adipose tissue stores fat, and muscles oxidize fatty acids for energy.

Which hormones regulate lipid metabolism?

Lipid metabolism is mainly regulated by insulin, glucagon, epinephrine, and cortisol. Insulin promotes lipid synthesis and storage, while glucagon and epinephrine stimulate lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation during fasting or stress.

What is β-oxidation and why is it important?

β-oxidation is the metabolic pathway through which fatty acids are broken down in mitochondria to produce acetyl-CoA, NADH, and FADH₂. It is important because it provides a major source of ATP when glucose availability is low.

What are ketone bodies and when are they produced?

Ketone bodies are water-soluble molecules produced in the liver during prolonged fasting, starvation, or uncontrolled diabetes. They serve as an alternative energy source for tissues such as the brain, heart, and muscles.

What happens when lipid metabolism is impaired?

Impaired lipid metabolism can lead to hyperlipidemia, obesity, fatty liver disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders. Inherited defects may cause severe metabolic problems, especially during fasting.

Why is cholesterol metabolism clinically important?

Cholesterol metabolism is important because excess cholesterol, especially LDL cholesterol, increases the risk of atherosclerosis and heart disease, while proper regulation supports hormone synthesis and cell membrane integrity.

Is lipid metabolism more important than carbohydrate metabolism?

Both are essential, but lipid metabolism becomes more important during fasting and prolonged energy demand, while carbohydrate metabolism dominates in the fed state. Together, they ensure metabolic flexibility and energy balance.

Conclusion

Lipid metabolism is a fundamental biochemical process that integrates the digestion, absorption, transport, synthesis, and oxidation of lipids to meet the body’s energy and structural requirements.

From the breakdown of dietary fats to the production of ATP through fatty acid oxidation (β-oxidation), and from fatty acid synthesis to cholesterol metabolism and ketone body formation, lipid metabolism ensures metabolic flexibility during both fed and fasting states.

A clear understanding of the steps of lipid metabolism, key enzymes, pathways, and regulatory mechanisms is essential for students of biochemistry, medicine, pharmacy, and life sciences.

The tight regulation of lipid metabolism by hormones such as insulin, glucagon, and epinephrine explains how the body switches between lipid storage and lipid mobilization.

Disruption of these pathways leads to lipid metabolism disorders, including hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, fatty liver disease, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome, highlighting the strong clinical relevance of this topic.

From an academic and clinical perspective, lipid metabolism is closely linked with carbohydrate metabolism, especially during fasting, starvation, and prolonged exercise, when lipids become the primary source of energy.

Mastery of lipid metabolism pathways, along with their clinical significance, not only helps in exam preparation but also provides a solid foundation for understanding metabolic diseases and their biochemical basis.

By revising lipid metabolism using clear pathways, comparison tables, diagrams, and clinical correlations, learners can strengthen both conceptual understanding and long-term retention—making this topic one of the most high-yield and essential areas of biochemistry.

Discover more from Biochemistry Den

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.